RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol: 15 Issue: 4 eISSN: pISSN

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Dr. Md Abdul Baseer, Department of Surgery, Khaja Banda Nawaz University, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India.

2Department of Radiodiagnosis, KIDWAI Memorial Institute of Oncology, VTSM PCC, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India.

3Department of Surgery, Khaja Banda Nawaz University, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India.

4Department of Surgery, Khaja Banda Nawaz University, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India.

5Department of Surgery, Khaja Banda Nawaz University, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India.

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Md Abdul Baseer, Department of Surgery, Khaja Banda Nawaz University, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India., Email: mabaseerdr@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Adrenal haematoma is an uncommon finding in blunt trauma, and isolated adrenal injuries are usually associated with low-impact accidents. The objective of this study was to determine the appropriate management protocol for adrenal haematoma in patients with severe abdominal blunt trauma.

Methods: This was a retrospective observational study conducted from March 2019 to February 2024, including all patients with a history of blunt trauma who demonstrated adrenal injury on contrast-enhanced CT (CECT). Data were collected and analyzed from the Medical Records Department.

Results: All 11 patients had adrenal haematoma, with seven cases on the right and four on the left. All patients were attended within six hours of injury. Eight patients had associated head injuries. Only one patient required surgery, while all others were managed conservatively. Follow-up at 1, 3, and 6 months showed that all patients were asymptomatic. The average duration of complete resolution of adrenal haematoma was three months.

Conclusion: Adrenal haematoma is generally self-limiting and can typically be managed non-operatively, depending on the patient’s haemodynamic status.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Trauma is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in younger populations worldwide, largely due to the rising population.1 It results in significant loss of workforce and human resources. Approximately 33% of all trauma patients sustain abdominal injuries, which require triaging for appropriate management. Among these, about 25% necessitate surgical intervention.2 Adrenal glands injuries are rare due to their small size, deep location in the retroperitoneum, and protection by the paraspinal muscles, rib cage, and liver.3,4 At autopsy, post-traumatic adrenal haematoma is seen in up to 25% of severely traumatized patients.5 Management may be surgical or conservative, depending on the extent of injury and the patient’s haemodynamic stability.3,6 The first report of an adrenal haematoma was documented in 1670 by Griselius of Vienna, according to Sevitt. Post-traumatic adrenal haematoma is an extremely rare condition, occurring in only 0.03%-2% abdominal trauma cases.7 It is most often associated with severe shock and concomitant injuries, and is unilateral in 75-90% of cases.8

Unilateral adrenal haematoma is usually clinically asymptomatic, whereas bilateral adrenal haematoma may lead to primary adrenal insufficiency, which, if untreated, can result in life-threatening adrenal crisis. With the increasing use of abdominal CT in patients with blunt trauma, the incidence of detecting unsuspected adrenal gland injuries, even after less severe trauma, has risen.9

The use of CT in trauma setting has changed substantially since the report by Burks et al., in 1992.10 With increasing recognition of its diagnostic accuracy, the clinical threshold for requesting CT has lowered, to an extent that even patients with minimal injuries may now undergo CT prior to discharge rather than being admitted for observation.11

Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective observational case series with clinical correlation. It was conducted at a tertiary care centre over a five-year period, from 1 March 2019 to 28 February 2024. Data were collected from the case sheets archived in the Medical Record Department. The following parameters were analyzed: demographic data, hemodynamic stability, blood transfusion, patient requiring ionotropic support, clinical presentation, management, hospital stay, follow-up and complications.

All patients with a history of blunt trauma who demonstrated adrenal haematoma on contrast enhanced CT (CECT) or abdominal ultrasound were included in the study.

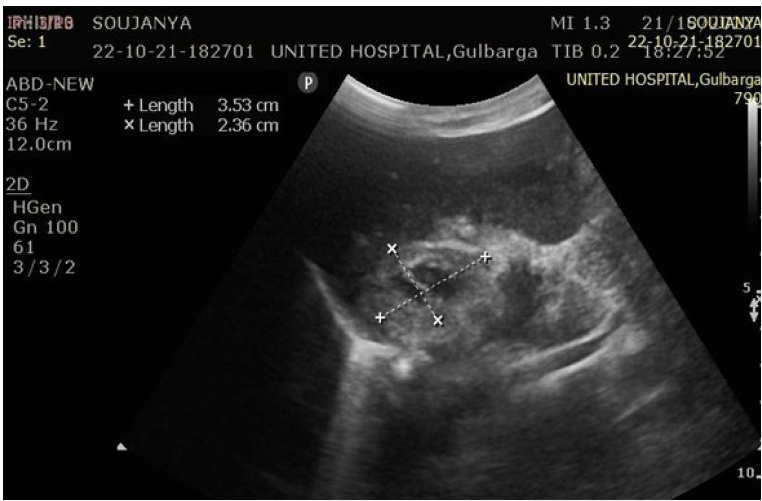

Ultrasonography (USG) evaluation

Ultrasonography was performed to assess adrenal haematomas with respect to site, size, mass effect, and appearance, categorized as early-stage or late-stage haematoma (Figure 1 and 2).

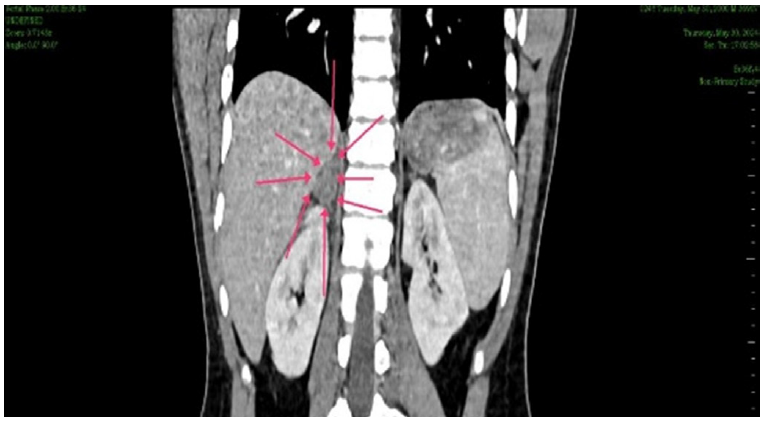

CT evaluation

CT scans were used to measure adrenal haematomas and classify them as irregular, oval, or circular. Other CT findings, including the enhanced area within the haematoma and associated injuries, were also evaluated (Figure 3 and 4).

Statistical analysis

Data were collected using a structured proforma, entered into MS Excel, and analyzed with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM, USA). Qualitative data were summarized in terms of proportions, while quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

A total of 11 patients with adrenal haematoma were detected on CECT abdomen. Of these, 8 were male and 3 were female. Seven haematomas were located on the right side and four on the left. All patients had a history of road traffic accident (RTA) with blunt abdominal trauma and were attended to within six hours.

Of the 11 patients with adrenal haematoma detected on CECT abdomen, two were haemodynamically unstable. One of these required blood transfusion and ionotropic support. Post-traumatic ileus occurred in five patients, among which three had liver injury, one had mesenteric injury, and one suffered renal injury. The patient with mesenteric injury was unstable, while the remaining nine patients were haemodynamically stable. Eight patients had associated head injuries. One patient with mesenteric injury required surgery, while all the others were managed conservatively. The average duration for initiation of oral feed was 2 ± 1 days, and the mean duration of hospital stay was 5 ± 2 days. One patient with adrenal haematoma who underwent surgery for mesenteric injury succumbed to death. None of the other patients had major complications. Follow-up was conducted at 1, 3, and 6 months. The average duration for complete resolution of adrenal haematoma was three months.

Discussion

There are relatively few studies in the literature of post-traumatic adrenal haematoma. Two mechanisms of injury have been proposed: 1. Direct trauma to the adrenal region during abdominal injury, leading to compression of adrenal gland against the spine; 2. Indirect trauma due to deceleration forces leading to arterial tears at the adrenal capsule level. Additional factors, such as stress, primary or iatrogenic haemostatic abnormalities, and pre-existing adrenal gland lesions, may also contribute to the development of adrenal haematomas, rather than the shock's intensity or deceleration alone.10

Two mechanisms have been proposed of traumatic adrenal gland injury. The first involves compression of the inferior vena cava (IVC), resulting in a sharp rise in intra-adrenal venous pressure. The predominance of right-sided adrenal injuries, consistent with the right adrenal vein's short length and its direct communication with the IVC, supports this theory.3 The second mechanism is the direct compression of the adrenal gland between the spine and surrounding organs during violent trauma, which correlates with the frequent occurrence of associated ipsilateral injuries. Pathologically, adrenal haematoma following trauma might present as peri-adrenal oedema, congestion, and minimal haemorrhage, or as intra-adrenal haematoma with distention but without rupture of the cortex.12,13

In our study of 11 patients with a history of road traffic accidents and blunt abdominal trauma, adrenal haematoma was detected on CECT. The spleen and liver are the most commonly injured solid organs in blunt abdominal trauma.1 Post-traumatic adrenal haematoma, by contrast, is rare, occurring in only 0.03% to 2% of abdominal trauma cases.7

The right-sided predominance of adrenal haematomas is attributed to the direct transmission of increased venous pressure from the inferior vena cava into the right adrenal vein, leading to congestion and rupture, as well as greater compression of the right adrenal gland between the liver and the spine.12 In our study, seven patients had right-sided adrenal haematoma, while four had left-sided involvement. Rana AI et al., reported that left adrenal haematomas were more often associated with left rib fractures, splenic injuries, and left renal injuries, whereas right adrenal haematomas were more common and more frequently associated with right rib fractures, hepatic injuries, and right renal injuries.11 The greater propensity for right adrenal haematomas may be further explained by the confined anatomical space of the right adrenal gland between the liver and spine, coupled with the greater mass of the liver.11

All patients in our study were attended to within six hours of injury. Two patients were haemodynamically unstable, one of whom required blood transfusion and ionotropic support. In the study by Rana AI et al., patients with adrenal haematomas had a significantly higher mortality rate compared with controls (10% vs 4%, P= .001).11 Among their cohort, 26 patients had one other visceral injury, while 16 had at least two additional visceral injuries, including 26 hepatic, 24 splenic, and 16 renal injuries. Isolated adrenal haematoma in trauma patients was rare; although nine patients had no other visceral injury, eight of these had substantial orthopaedic, chest, or head injuries, and only one presented with adrenal haematoma alone.11 In our study, five patients developed post-traumatic ileus, of which three were associated with liver injury, one with mesenteric injury, and one with renal injury. The patient with mesenteric injury was unstable, while the remaining nine patients were haemodynamically stable. Additionally, eight patients sustained associated head injuries.

Adrenal haematomas may be managed either operatively or non-operatively, depending on the extent of injury, status of the contralateral adrenal gland, viability of residual adrenal tissue, the patient’s overall condition, and associated injuries. Adrenalectomy should be reserved for cases of extreme parenchymal damage, particularly when the contralateral gland has been previously resected. Surgical options include: preservation of gland and prevention of adrenal insufficiency; total resection of adrenal gland, which eliminates the source of delayed haemorrhage or infection and reduces the risk of inferior vena cava thrombosis due to compression.3 In our study, only one patient with associated mesenteric injury underwent surgery, while all others were managed conservatively.

In adrenal trauma, ultrasound often demonstrates an echogenic adrenal mass, with a subsequent decrease in size on follow-up ultrasonic examinations.14 Iuchtman and Breitgand reported that ultrasonic imaging is a useful initial diagnostic tool; however, CT remains superior for delineating the extent of injury.15

In our study, the mean time to initiation of oral feeding was 2 ± 1 days, and the mean duration of hospital stay was 5 ± 2 days. One patient with adrenal haematoma who underwent surgery for mesenteric injury succumbed to death. In contrast, Rana AI et al., reported that patients with adrenal haematoma were hospitalized and the hospital stays ranged from 1 to 370 days (mean, 24.79±53.8 days). Among them, 36 of 51 patients required intensive care, with lengths of stay ranging from 1 to 48 days (mean 10.6±13.4 days).11

Conclusion

In our study, none of the remaining patients developed major complications. All haemodynamically stable patients were managed conservatively. Follow-up was conducted at 1, 3, and 6 months, with complete resolution of adrenal haematoma observed at an average of three months.

Conflict of Interest

None

Source of Support

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. Isenhour JL, Marx J. Advances in abdominal trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2007;25(3):713-33.

2. Alastair CJ, Pierre JG. Abdominal trauma. In: John M, Graeme D, Kevin OM, editors. Surgical Emergencies, 1st edition. Italy: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1999. p. 224-36.

3. Gomez RG, McAninch JW, Carroll PR. Adrenal gland trauma: diagnosis and management. J Trauma 1993;35: 870-874.

4. Murphy BJ, Casillas J, Yrizarry JM. Traumatic adrenal hemorrhage: Radiologic findings. Radiology 1988;169(3):701-3.

5. Wilms G, Marchal G, Baert A, et al. CT and ultra-sound features of posttraumatic adrenal hemorrhage. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1987;11(1):112-5.

6. Rammelt S, Mucha D, Amlang M, et al. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 2000;48:332-5.

7. Sevitt S. Post-traumatic adrenal apoplexy. J Clin Pathol 1955;8:185-194.

8. Roberts JL. CT of abdominal and pelvic trauma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1996;17(2):142-169.

9. Scully RE, Mark EJ, McNeely BU. Hypertension and an adrenal mass after a vehicular accident. N Engl J Med 1984;311:783-790.

10. Burks DW, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Acute adrenal injury after blunt trauma: CT finding. Am J Roentgenol 1992;158:503-507.

11. Rana AI, Kenney PJ, Lockhart ME. Adrenal gland hematomas in trauma patients. Radiology 2004;230(3):669-675

12. Sevitt S. Post-traumatic adrenal apoplexy. J Clin Pathol 1955;8(3):185-194.

13. Greendyke RM. Adrenal hemorrhage. Am J Clin Pathol 1965;43:210-215.

14. Wilms G, Marchal G, Maert A, et al. CT and ultrasound features of post-traumatic adrenal hemorrhage. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1987;11: 112-115.

15. Iuchtman M, Breitgand A. Traumatic adrenal hemorrhage in children: an indicator of visceral injury. Pediatr Surg Int 2000;16(8):586-588