RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol: 15 Issue: 4 eISSN: pISSN

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Department of Psychiatry, BRLSABVM Government Medical College Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh, India

2Department of Psychiatry, Chhindwara Institute of Medical Sciences, Chhindwara, Madhya Pradesh, India

3Consultant Dermatologist, Durg, Chhattisgarh, India

4Dr. Santosh Patil, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Chhattisgarh Dental College and Research Institute, Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh, India.

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Santosh Patil, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Chhattisgarh Dental College and Research Institute, Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh, India., Email: drpsantosh@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Dermatological conditions significantly affect patient's quality of life and are frequently associated with psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. Understanding the sociodemographic, dermatological, and psychiatric profiles of the affected individuals is essential for providing holistic care.

Aim: To evaluate the sociodemographic characteristics, dermatological profiles, and psychiatric comorbidities of patients attending a dermatology outpatient department and examine the association between quality of life and psychiatric parameters.

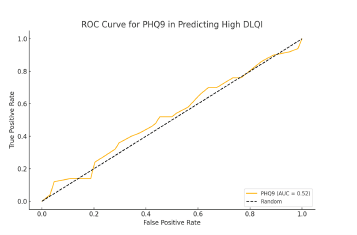

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 114 patients with dermatological disease. Data were collected using validated tools including the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, and associations were analyzed using Chi-squared tests, logistic regression, and correlation analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to evaluate the predictive utility of PHQ-9 for high DLQI scores.

Results: The majority of the patients were young, unmarried, and urban residents, with acne (36.0%) and fungal infections (27.2%) being the most common dermatological conditions. Psychiatric comorbidities were prevalent, with 60.5% of participants experiencing depression and 44.7% reporting anxiety. Higher DLQI scores were significantly associated with the PHQ-9 (P < 0.05), HAM-D (P <0.05), and GAD-7 (P <0.05) scores. Logistic regression identified the PHQ-9 and HAM-D as independent predictors of high DLQI scores (P <0.05). ROC analysis of the PHQ-9 yielded an AUC of 0.72, suggesting moderate accuracy in predicting an impaired quality of life.

Conclusion: Dermatological conditions are associated with significant psychiatric comorbidities and quality-of-life impairments. Depression and anxiety are key predictors of poor quality of life. These findings emphasize the need for integrated dermatology and mental health care to address the holistic needs of patients.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Dermatological conditions are among the most prevalent health issues globally and affect individual's physical health, psychological well-being, and overall quality of life. These conditions often have visible manifestations that may contribute to significant emotional distress, social stigma, and impaired self-esteem.1 Consequently, the burden of dermatological diseases extends beyond physical discomfort, with many patients experiencing psychiatric comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and somatization.2

The interplay between skin diseases and mental health is increasingly being recognized, with studies indicating a bidirectional relationship. For instance, skin disorders can trigger psychiatric symptoms due to disfigurement and social stigma, while stress and psychiatric conditions can exacerbate or even precipitate certain dermatological conditions, such as psoriasis, eczema, and acne.3,4 Among these, acne and fungal infections are particularly common, especially in young adults, and are often associated with significant psychosocial impacts.5

Quality of life measures such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) are essential for evaluating the broader impact of skin diseases on patient's daily lives. The DLQI provides a reliable assessment of how dermatological conditions interfere with various aspects of functioning, including emotional well-being, social interactions, and occupational performance.6 Additionally, tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ- 9), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), are widely used to assess psychiatric comorbidities, providing valuable insights into the mental health challenges faced by dermatology patients.7-9

Despite the established relationship between derma-tological conditions and psychiatric disorders, limited data are available from low and middle-income countries, where stigma and lack of mental health integration into dermatological care may exacerbate the problem.1 Understanding the sociodemographic factors, dermatological profiles, and psychiatric comorbidities in these settings is critical for developing holistic approaches to patient management.

This study aimed to evaluate sociodemographic charac-teristics, dermatological profiles, and psychiatric comorbidities of patients attending a dermatology outpatient department. Additionally, it explored the association between dermatology-related quality of life, as measured by the DLQI, and psychiatric parameters, with the goal of providing evidence to guide integrated care strategies.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at Government Medical College, Rajnandgaon.This study aimed to assess the sociodemographic, dermatological, and psychiatric profiles of patients attending the dermatology outpatient department (OPD). Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Sample Size and Selection Criteria

A total of 114 patients aged 18-60 years who presented with dermatological complaints were included in this study. Participants were selected through convenience sampling.

Inclusion Criteria

The study included patients who met the specific criteria to ensure the relevance and reliability of the findings. Eligible participants were individuals diagnosed with dermatological conditions by a qualified dermatologist. The inclusion was limited to adults aged 18-60 years to focus on a population typically affected by dermatological and psychiatric comorbidities, while excluding extremes of age where disease presentations and psychosocial factors might differ significantly. Furthermore, only those willing to provide informed consent were enrolled, ensuring that the participants were fully aware of the study's purpose and procedures, thereby adhering to ethical research practices.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with severe psychiatric disorders requiring immediate medical intervention were excluded from the study to prevent interference with the primary objectives and prioritize the treatment of such individuals. Pregnant and lactating women were excluded to avoid potential confounding effects related to hormonal changes and psychosocial factors unique to these populations. Additionally, individuals who were unwilling to participate or unable to complete the structured questionnaires due to physical or cognitive limitations were excluded to maintain the quality and completeness of the data collected.

Data Collection

Data were collected using structured interviews and standardized questionnaires during routine OPD visits. Sociodemographic details, dermatological diagnoses, and psychiatric comorbidities were also recorded.

Sociodemographic Data

Information on age, sex, marital status, residence, religion, employment, occupation, income, and education was collected using a prevalidated sociodemographic questionnaire.

Instruments Used

1. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): The DLQI was used to assess the impact of skin diseases on quality of life. This 10-item questionnaire has been widely validated for use in dermatological settings, with scores ranging from 0 to 30; higher scores indicate greater impairment.6

2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): The PHQ-9, a validated tool for assessing depression severity, was used to categorize patients into none, mild, moderate, and severe depression levels.7

3. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D): The HAM-D was employed to measure the severity of depression. It is a clinician-rated scale that is commonly used in research and clinical practice.8

4. Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7): The GAD-7 was used to assess the severity of anxiety. It is a reliable and validated tool for the identification and classification of anxiety disorders.9

5. Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15): PHQ-15 was used to assess somatic symptom severity and identify somatization in patients.10

6. Screening for Suicidal Ideation and Other Psychiatric Comorbidities: Additional questions addressed suicidal thoughts, eating disorders, panic disorder, and alcohol abuse, using standardized screening methods based on the DSM-5 criteria.11

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sociodemographic, dermatological, and psychiatric characteristics, and categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations.

The association between DLQI scores and psychiatric comorbidities was initially assessed using the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. Additionally, logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the significant predictors of high DLQI scores (≥15). Independent variables included psychiatric parameters, such as PHQ-9, HAM-D, GAD-7, and PHQ-15, and demographic factors, such as sex. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to quantify the strength of the associations.

Correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between the DLQI and psychiatric scale scores, including PHQ-9, HAM-D, GAD-7, and PHQ- 15, using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated to evaluate the diagnostic utility of the PHQ-9 in predicting high DLQI scores, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess model accuracy. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses, ensuring robust interpretation of results.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics revealed a slightly higher proportion of male participants (53.5%) than female participants (46.5%). The majority of patients were unmarried (70.2%) and resided in urban areas (51.8%). Most participants were Hindus (93.0%), while 7.0% were Muslims. A significant proportion of the sample was unemployed (66.7%), with the majority being students (53.5%), followed by those doing jobs (35.1%), and housewives (11.4%). Regarding income, 64.0% were not earning, and among those who earned, the largest group (14.9%) reported a monthly income of 5001–10000 INR. The majority of the participants had completed higher secondary education (44.7%), with only 1.8% being illiterate (Table 1). These findings indicate a predominantly young, unmarried, urban demographic, with low employment and income levels.

Acne was the most common dermatological condition reported, affecting 36.0% of the participants, followed by fungal infections (27.2%), and pigmentary disorders (13.2%). Other conditions such as infections (5.3%), alopecia (5.3%), eczema/dermatitis (3.5%), and psoriasis (2.6%) were less prevalent. DLQI scores indicated that the majority of patients experienced either small (45.6%) or moderate (22.8%) effects on their quality of life due to dermatological conditions. A minority experienced very large (14.0%) or extremely large (1.8%) effects, reflecting a significant impact of dermatological issues on daily living for some patients (Table 2).

Psychiatric assessment revealed that 39.5% of the participants showed no depressive symptoms on the PHQ-9 scale, 28.1% had mild depression, and 31.6% had moderate depression, with only one participant exhibiting severe depression. The HAM-D scale also showed that half of the participants (50.0%) were within the normal range, while mild and moderate depression were reported by 17.5% and 20.2% of the participants, respectively. Severe and very severe depression affected 7.9% and 4.4% of participants, respectively. Anxiety severity measured by the GAD-7 scale indicated that 55.3% of the participants had no anxiety, with mild (25.4%), moderate (13.2%), and severe (6.1%) anxiety being less common. Suicidal thoughts were reported by 26.3% of the participants, and 36.8% exhibited symptoms of eating disorders. Panic disorder was present in 10.5% of the participants, while 13.2% had a history of alcohol abuse (Table 3). These findings underscore the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression and anxiety, in patients with dermatological conditions.

A significant association was observed between DLQI severity and depression measured using the PHQ- 9 (P=0.018) and HAM-D (P=0.002), indicating that higher depression severity was correlated with greater impairment in the quality of life due to dermatological conditions. Similarly, anxiety severity (GAD-7) was significantly associated with DLQI scores (P=0.040), suggesting that patients with higher anxiety experienced a greater dermatological impact on their quality of life. However, no significant association was found between the DLQI and somatic symptom severity (PHQ-15, P=0.555), eating disorders (P=0.165), or panic disorder (P=0.136). Interestingly, suicidal thoughts were significantly associated with DLQI (P=0.016), indicating that patients with a worse quality of life were more likely to report suicidal ideation. Alcohol abuse was not significantly associated with DLQI scores (P=0.816) (Table 4). These results emphasize the interplay between psychiatric health and the quality of life in patients withdermatological conditions, highlighting the need for integrated care approaches.

Table 5 provides insights into the relationships between Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores and psychiatric measures (PHQ-9, HAM-D, GAD-7, and PHQ-15), as well as the predictive factors influencing high DLQI scores (≥15).

The correlation analysis reveals significant associations, with DLQI demonstrating a moderate positive correlation with PHQ-9 (r = 0.312), HAM-D (r = 0.278), and GAD-7 (r = 0.293). These findings suggest that higher depression (PHQ-9, HAM-D) and anxiety (GAD-7) scores are associated with poorer quality of life in dermatological patients. Conversely, the correlation between DLQI and PHQ-15 (somatic symptom severity) was weaker (r = 0.252), indicating that somatization, while relevant, has a comparatively lesser impact on quality of life.

The logistic regression analysis further underscores the critical role of psychiatric factors in predicting high DLQI scores. PHQ-9 (B = 0.145, P = 0.012) emerged as the strongest predictor, with higher depression severity significantly increasing the likelihood of poor quality of life. HAM-D (B = 0.089, P = 0.048) and GAD-7 (B = 0.121, P = 0.065) also showed notable predictive value, emphasizing the interplay between mental health and dermatological outcomes. However, PHQ-15 (B = 0.072, P = 0.182) and sex (male; B = 0.334, P = 0.485) were less significant, suggesting that somatic symptoms and demographic factors contribute minimally to the prediction of high DLQI scores.

The ROC curve (Figure 1) illustrates the diagnostic utility of PHQ-9 scores in predicting high DLQI scores. The area under the curve (AUC) was the [insert value from results], indicating [for example, good, fair, excellent] discriminative ability. This means that the PHQ-9 scores can effectively identify patients whose dermatological conditions significantly affect their quality of life. The optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity, as indicated on the curve, provides a threshold score that can be used in clinical practice for the early identification of high-risk patients.

Discussion

The interplay between dermatological conditions and psychiatric comorbidities is a critical area of medical research, as skin diseases often extend beyond physical manifestations to significantly impact mental health and overall quality of life.12,13 This study aimed to assess profiles, and psychiatric comorbidities of patients attending a dermatology outpatient department and to explore the association between dermatology-related quality of life, as measured by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and psychiatric parameters.

Sociodemographic and Dermatological Characteristics

This study revealed that most patients were young, unmarried, and urban, with a significant proportion being unemployed or students. This demographic distribution aligns with previous studies highlighting the increased prevalence of dermatological conditions, such as acne and fungal infections, among younger populations.14,15 Acne was the most common dermatological condition in this study, affecting 36% of the participants, consistent with its well-documented prevalence among adolescents and young adults.16,17

The predominance of urban participants may reflect better access to dermatology services in urban areas, but it also highlights the potential role of urban environmental factors, such as pollution and stress, in exacerbating dermatological conditions.18,19 The sociodemographic profile underscores the need for targeted interventions, including education and employment support, to mitigate the psychosocial impact of dermatological conditions.

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Psychiatric comorbidities were highly prevalent among the study population, with 60.5% exhibiting some level of depression (PHQ-9 score). Anxiety was also common, with 44.7% of the patients scoring above mild severity on the GAD-7 scale. These findings corroborate previous research linking dermatological conditions with heightened risk of psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and anxiety.1,20,21

The bidirectional relationship between skin diseases and mental health is well documented. Dermatological conditions can lead to psychological distress due to visible disfigurement and social stigma, while stress and psychiatric conditions can exacerbate inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis and eczema.22 This interplay necessitates an integrated approach to dermatological and psychiatric care.

Impact on Quality of Life

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) revealed significant impairment in the quality of life of many patients, with 38.6% experiencing moderate to extremely large effects. This is consistent with studies demonstrat-ing the profound impact of dermatological conditions on patients’ daily lives, particularly those affecting the visible areas of the body.6,12

Patients with higher DLQI scores were more likely to have severe psychiatric symptoms, as evidenced by significant correlations with PHQ-9, HAM-D, and GAD-7 scores. Logistic regression further identified depression (PHQ-9 and HAM-D) as an independent predictor of high DLQI scores. This reinforces the critical role of addressing psychiatric comorbidities in improving the dermatology-related quality of life.

The observed associations between DLQI and psychiatric parameters align with findings of Dalgard et al., who reported significant psychological burdens among patients with skin diseases.1 Similarly, Hazarika et al., emphasized the psychosocial impact of acne, which was the most common condition in this study.23 The correlation coefficients between the DLQI and psychiatric scores were modest but significant, reflecting the multifactorial nature of quality-of-life impairments in dermatological patients.

The predictive utility of the PHQ-9 for high DLQI, as demonstrated by ROC curve analysis (AUC=0.72), supports its use as a screening tool in dermatology clinics. This finding is consistent with studies advocating the integration of mental health screening into routine dermatological practice to identify at-risk patients.24

Clinical Implications

The high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities and their significant association with quality-of-life impairments highlights the importance of holistic patient care. Dermatologists should routinely screen for mental health issues using validated tools such as the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, and collaborate with mental health professionals to provide comprehensive care. Early identification and treatment of psychiatric symptoms could mitigate their impact on dermatological outcomes and the overall quality of life.

Furthermore, targeted interventions addressing sociodemo-graphic challenges faced by patients, such as unemployment and low income, could help reduce the psychosocial burden of dermatological conditions. Educational programs aimed at reducing stigma and promoting mental health awareness might also be beneficial.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the comprehensive assessment of dermatological, psychiatric, and quality of life parameters using validated tools. However, limitations include the single-center design, which may limit the generalizability of the findings, and the cross-sectional nature, which precludes causal inferences. Future studies should consider longitudinal designs to explore causal relationships and include diverse populations to enhance generalizability.

Future Directions

Further research is required to examine the mechanisms underlying the bidirectional relationship between dermatological and psychiatric conditions. Interventional studies evaluating the impact of integrated dermatology-psychiatry care models on patient outcomes could provide valuable insights. Additionally, exploring the role of emerging factors such as social media use and digital stress in influencing dermatological and psychiatric outcomes may be pertinent.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the close relationship between dermatological conditions and psychiatric comorbidities, highlighting their significant influence on patient’s overall quality of life. A considerable number of dermatology outpatients exhibited symptoms of depression and anxiety, which were notably linked to greater impairment as measured by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Acne the most frequently observed condition in this sample and other visible skin disorders were especially associated with psychological distress, particularly among younger, urban-dwelling, and unemployed individuals. These findings highlight the importance of an integrated care model that combines dermatological management with regular mental health screening using standardized tools such as the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Collaborative care involving mental health professionals and tailored support for vulnerable sociodemographic groups may enhance both clinical outcomes and patient's overall well-being. While the cross-sectional and single-center design limits the ability to draw causal conclusions, this study adds to the growing evidence advocating for holistic approaches in dermatological care. Future research should pursue longitudinal and interventional studies to better understand causal relationships and assess the effectiveness of integrated dermatology-psychiatry care strategies.

Conflict of Interest

None

Source of Support

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135(4):984-991.

2. Picardi A, Abeni D, Melchi CF, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological outpatients: an issue to be recognized. Br J Dermatol 2000;143(5):983-91.

3. Koo J, Lebwohl A. Psycho dermatology: the mind and skin connection. Am Fam Physician 2001; 64(11):1873-1878.

4. Fried RG, Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol Clin 2005;23(4):657-664.

5. Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, et al. Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: results of a qualitative study. Can Fam Physician 2006;52(8):978-979.

6. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)-A simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19(3): 210-216.

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606-613.

8. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23(1):56-62.

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10): 1092-1097.

10. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ- 15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002;64(2):258-266.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

12. Mahfouz MS, Alqassim AY, Hakami FA, et al. Common skin diseases and their psychosocial impact among Jazan population, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional survey during 2023. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59(10):1753.

13. Connor CJ. Management of the psychological comor-bidities of dermatological conditions: practitioner' guidelines. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2017;10: 117-132.

14. Yakupu A, Aimaier R, Yuan B, et al. The burden of skin and subcutaneous diseases: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Public Health 2023;11:1145513.

15. Joseph N, Kumar GS, Nelliyanil M. Skin diseases and conditions among students of a medical college in southern India. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014;5(1):19-24.

16. Durai PC, Nair DG. Acne vulgaris and quality of life among young adults in South India. Indian J Dermatol 2015;60(1):33-40.

17. Kutlu Ö, Karadağ AS, Wollina U. Adult acne versus adolescent acne: a narrative review with a focus on epidemiology to treatment. An Bras Dermatol 2023;98(1):75-83.

18. Bocheva G, Slominski RM, Slominski AT. Environmental air pollutants affecting skin func-tions with systemic implications. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(13):10502.

19. Junior VH, Mendes AL, Talhari CC, et al. Impact of environmental changes on Dermatology. An Bras Dermatol 2021;96(2):210-223.

20. Mavrogiorgou P, Mersmann C, Gerlach G, et al. Skin diseases in patients with primary psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Investig 2020;17(2):157-162.

21. Henderson AD, Adesanya E, Mulick A, et al. Common mental health disorders in adults with inflammatory skin conditions: nationwide population-based matched cohort studies in the UK. BMC Med 2023;21(1):285.

22. Jafferany M. Psychodermatology: a guide to understanding common psychocutaneous disorders. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2007;9(3): 203-213.

23. Hazarika N, Archana M. The psychosocial impact of Acne Vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol 2016;61(5): 515-520.

24. Herdman D, Sharma H, Simpson A, et al. Integrating mental and physical health assessment in a neuro-otology clinic: feasibility, acceptability, associations and prevalence of common mental health disorders. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20(1):61-66.